| Main Page Sponsors Implementation Exhibits Demos/Images Poetry Credits Articles Web Links |

This is adapted from a paper presented at the COSIGN 2001 Conference, September 10-12, 2001 in Amsterdam, Holland. Beyond Manzanar: Constructing Meaning

| |

ABSTRACTBeyond Manzanar is an interactive 3D virtual reality artwork. It is written in VRML and runs off the hard drive of a fast gaming PC. It is shown as a room installation with the image projected life-sized on a large screen. One user at a time can navigate through the 3D environment in first-person viewpoint using a simple joystick; other can watch and share the experience. The piece explores parallels between experiences of Japanese Americans imprisoned at the Manzanar Internment Camp in Eastern California during World War II, and Iranian Americans threatened with a similar fate during the 1979-'80 hostage crisis. The physical environment of Manzanar, strikingly similar to the landscapes of Iran, creates a poetic bridge between two groups linked by the experience of being "the face of the enemy." Beyond Manzanar is an exploration of the capabilities of virtual reality to provide a strong dramatic structure and still involve users in creating their own narrative, adding a sense of participation and responsibility for the events that happen to them in the course of their explorations. INTRODUCTIONThe interactive virtual reality work Beyond Manzanar uses navigable 3-D graphics

running on a fast gaming PC to simulate the Manzanar Internment Camp in California,

USA, transformed by dreams and memories. The piece explores parallels between

experiences of Japanese Americans interned at the camp during World War II and

Iranian Americans threatened with a similar fate during the 1979-'80 hostage crisis.

[1] Beyond Manzanar was a joint project between myself, an American visual artist of mixed Japanese/German ancestry, and Zara Houshmand, an Iranian American theater director and poet. Both Zara and I had worked as creative directors at Worlds, Inc. in San Francisco, one of the first companies to bring out a commercial platform for real-time PC-based virtual reality. We were well acquainted with the technical capabilities of the medium from our commercial work and wished to explore the dramatic possibilities of the medium in a pure art piece. We used theories of dramatic structure taken from theater, music composition and urban design to create an experience with a strong narrative structure. Within this structure, the interactive technology gives users freedom to find their own way through the environment and make their own discoveries. Their movements through 3D space translate them across time and cultures as the environment senses their presence and transforms around them. The first-person viewpoint and interactivity of the piece require users to take emotional responsibility for their decisions and the consequences. In the end, however, this is art and not life. We let the software loop to allow users to return and relive the spaces, now transformed into part of their own memories. CONTENT AND BACKGROUNDManzanar, an oasis in the high desert of Eastern California, was the first of over 10 internment camps erected during World War II to incarcerate Japanese American families solely on the basis of their ancestry. Though this specific instance was ruled "not justified" in 1988, mass internment of an entire group without due process "in cases of military necessity" is still legal. Ethnic groups whose countries of origin are considered rogue states by the American government can legally be interned without trial if tensions between the countries escalate into violence. In 1979 during the Iranian hostage crisis there were physical attacks on Iranian Americans and calls to intern and deport them to Iran, regardless of their personal stances towards the hostage crisis. For an Iranian American, Manzanar is an especially ironic symbol of the threat of internment: the site itself is hauntingly reminiscent of the landscapes of Iran. The grid of roads drawn in the desert by the military echoes the geometric order of an Iranian paradise garden - a further irony, for the Japanese Americans did indeed create gardens, an ancient form of virtual reality, within the barbed wire fences. Manzanar is therefore the ideal symbolic site for a metaphorical exploration of parallels between the wartime experiences of Japanese-Americans and current discrimination against Iranian Americans as "the face of the enemy." INSTALLATION AND INTERFACE |

|

|

Beyond Manzanar is shown as a room installation with the image projected life-sized on a wall. This creates the feeling of an immersive virtual space while still allowing groups of people to view the piece together. It is written in VRML and runs using the blaxxun Contact 4.4 browser plug-in to Internet Explorer. Due to the large number of relatively large texture maps (256x256 pixels and some 512x512 pixels) it requires an AGP graphics card with minimum 32 MEG of graphic RAM and a fast processor with at least 256 MEG of system RAM. One user at a time can control a simple, small joystick that moves the user in first-person viewpoint through the virtual space. There is only one path through the piece and the piece will loop indefinitely as long as the user keeps moving forward through the scenes. A user can leave at any time; the next user takes over the joystick and starts where the previous user left off. |

Figure 1. Installation View |

|

It was important to me to keep the interface and interaction simple, since an important part of our audience is former wartime internees. Even the youngest of them are now over 55 and the great majority have no experience playing 3D games such as Doom or Quake. I chose a joystick as the interface with the reasoning that it is the interface device used by handicapped people to steer motorized wheelchairs through real 3D spaces, and should be relatively easy for a variety of people to use in virtual space as well. I am delighted to be able to report seeing many little old ladies jumping at the chance to gain control of the joystick, and of course their youngest grandchildren and great-grandchildren are equally adept, if not more so. CREATING EMOTIONAL AFFECTMy personal technical interest in creating this piece was to experiment with the volitional and kinesthetic possibilities of VR, which for me meant that users should be free to explore and find their own way through the piece rather than be presented automatically with linear content or by such obvious affordances as a "next" button. I wished also to utilize the possibilities for full immersion and full identification inherent in a first-person viewpoint. This creates a challenge: how could we give the piece a strong dramatic character while still allowing the users to construct their own narrative? The known weakness of using a first-person viewpoint, mentioned for instance by Andy Clarke and Grethe Mitchell, [2] is the difficulty of creating narrative interest when there is only a single camera viewpoint. Neither film, theater nor dance theory provided me with insight into dealing with these problems. Theory from these fields tends to be character centered and deal with the development of dramatic tension between characters seen mostly in third-person viewpoint. Viewers see the work from a single fixed seat in a theater and the director therefore has quite a lot of control over what is visible in any given scene. I surmised that with a first-person viewpoint, character development has to happen essentially within the users themselves as they explore the virtual environment. This means composing the piece from the perspective of the emotional states roused in users by their interactions with the piece itself. Brenda Laurel's work [3] provides interesting insights in both drama theory and its application to a more "human centered" form of interaction between human and computer, but I felt I needed a more abstract or fundamental theory that provided insight into composing the discrete units of the piece. I looked to the more abstract realms of time-based media theory: music and urban planning. If music can provoke powerful emotional reactions and the feeling of deep meaning in the listener merely by arranging abstract notes in certain structures, it must be possible to do the same in any other medium as well. Leonard B. Meyer [4] addresses this phenomenon directly, proposing the thesis (to vastly simplify his argument) that music provokes emotional responses in listeners by arousing expectations and then playing with these expectations in various ways: fulfilling them, disappointing them, surprising them or by delaying their resolution. The composer creates a sense of meaning in the listener by bringing these various emotions to a resolution and conclusion by the end of the piece. Focusing on the emotional states of a first-person protagonist was a familiar concept for me: my father, Philip Thiel, preaches this method in his work on urban environments, providing theory and tools for both analyzing and designing sequential urban spaces from the viewpoint of a person walking through the environment. [5] His analysis dissects an environment into the following components: Space: the physical landscape itself (plains, mountains, rivers, etc.) Place: the built environment created by human beings (buildings, roads, etc.) Occasion: what people are doing in this place at a specific time (sitting in a cafe, holding a demonstration, etc.) In Beyond Manzanar, the space is the Manzanar landscape, represented by its characteristic background mountain panorama. The space always remains the same but the place changes: sometimes an internment camp, sometimes a paradise garden. Each built environment affects not only what can be "done' in the space - the occasion - but also the user's emotional relationship to the space. The same mountain panorama produces a different emotional affect depending on whether it is seen framed by a paradise garden or by barracks and guard towers. This fact forms the basis of the dramatic structure of our piece. In this paper I will refer to a specific combination of place and occasion as a scene. Each scene was designed from the perspective of the emotions that it should evoke in the user. Each scene has an emotional "ground note:' it should evoke either negative or positive emotions, for instance a feeling of alienation or of security. The sequence in which the scenes are concatenated is carefully arranged in the same way that a music composer arranges phrases to create dramatic structure within a piece of music, complementing or alternating emotional states, building suspense or releasing it dramatically. As the user becomes more experienced with the piece, looping through several times as many users do, the element of surprise is reduced but also replaced with the element of anticipation. CREATING NARRATIVE IN A SCENECreating an environment or building in VR, whether an historical reproduction or a new fantasy, can produce an impressive stage set. For an artwork this is not enough, however. It must somehow be filled with the culture of those who built it, real or imagined; otherwise it remains an empty shell. If it replicates a real environment it should also use the characteristics of the technology to provide an experience that is impossible to get from visiting the real site. This for me is the excitement of virtual reality: it provides an excellent platform for creating gesamtkunstwerke in which an environment is brought to life by the inclusion of other material such as sound, images and texts (and for that matter other characters in the form of avatars.) |

|

| Thus the WWII camp scene in the piece makes extensive use of images and sounds from the Manzanar Internment Camp. The barracks are reconstructed from archival photographs and military data, but to emphasize their emotional effect and physical presence they are slightly larger than life-size, as adult internees tended to be very much smaller than the average height today. To emphasize that real people were involved and to give a sense of the conditions under which they lived in mass confinement, the windows of the barracks are filled with historic photographs showing daily life of the internees at Manzanar. To underscore a sense of personal loneliness, the only sounds are a woman's voice singing from the barracks and the crunch of ghostly footsteps - and of course the incessant, mournful desert wind. |

Figure 2. Camp Life |

| To make it clear that this piece is not a documentary but a mixture of "what has been" and "what could be" we consciously emphasized the surreal to create the feeling of being in a dream. We found that virtual reality lends itself to visualization of figures of speech: in the sky above the internment camp, headlines from the war and anti-Japanese signs slowly fade in and out to literally fill the air with hate. It is important that the signs are not always there; sometimes the air is clear, which makes it that much more oppressive when the sky again fills with hate and foreboding. |

Figure 3. Signs of Antipathy |

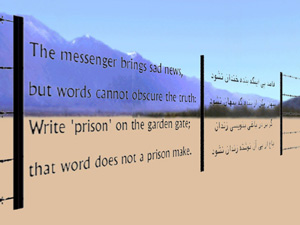

| Another way to increase the dramatic impact of a scene is to play cat-an-mouse with users and their emotional relationship to the space. The "quiet" scene where the piece starts (or re-starts) shows the empty landscape of present day Manzanar: mountain panoramas and a grid of roads through the desert scrub. The space seems unbounded and open, but if users try to "run away' a barbed-wire fence materializes in front of them. The physical object is enhanced with cultural content: the barbs of the fence are poems about exile written in English, Farsi (Iranian) and Japanese, some actually written by Japanese Americans in other camps, some from classical Japanese and Iranian literature. The user stands at the fence, confronted with a narrative voice that underscores the visual and physical message of the fence: You are a prisoner. |

Figure 4. Rumi Fence-Poem |

| A feature of virtual reality that has strong dramatic possibilities is to play with the vertical dimension. One example in our piece is within the American Dream sequence, where the seemingly solid walls and floors of a room become transparent to leave the user hovering in the air above an internment camp. With this and all such technical effects it is important that they be used only when they reinforce the narrative of the piece, never merely for their spectacular visual effect. |

Figure 5. Above the Void |

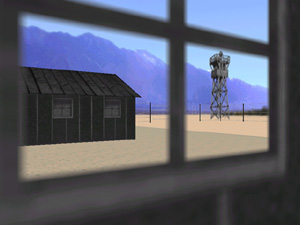

DRAMA IN SEQUENCES OF SCENESScenes are linked by open doors or paths that function as portals into the next scene, an intuitive clue even for inexperienced users. In order to make it work, however, I had to make a harsh decision: once you go through, the door slams shut behind you. The first time this happens it is of course a surprise and a frustration. It is however also a very important part of the message of the piece: in real life, there is no going back either. You have made a decision and must live with the consequences, even if you did not realize what would happen. Alternation between emotionally positive and emotionally negative scenes is the crux of the dramatic composition of the piece as a whole. In one scene, for example, users are inside a barrack but can look out the window to see the mountains of Manzanar framed by other barracks and the guard towers. |

Figure 6. View Out of the Barrack Window |

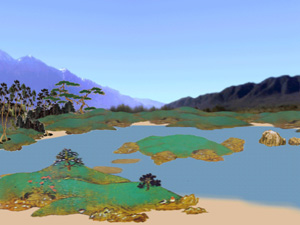

| If the users then enter a Japanese-style room within the barrack, the barrack - and indeed the entire camp - disappears to be replaced by a pavilion in a Japanese garden. In the garden I used the traditional captured scenery technique to visually integrate the mountain panorama: the eye sweeps out over a pond, continues over the trees and to the far mountains. In the context of the camp the mountains had formed a formidable barrier beyond the fence; in the context of the garden they lead the eye and spirit up and beyond, uniting the man-made garden with the timeless beauty of the natural world. |

Figure 7. Japanese Paradise Garden |

|

This sense of unity with nature is deceptive and temporary, a momentary dream in the dull reality of camp life. Once users begin to explore the garden, they will inevitably trip a trigger that throws them out of the garden and back into camp. The mountains return to their role as a formidable barrier on the horizon. The scenery stays the same, the view is the same, but the user's emotional relationship to it changes. Users are left with the feeling of responsibility, however inadvertently, for having destroyed the dream of the garden. There is no going back, the memory of the garden must suffice as the users move forward to confront the next scene. They are forced to be complicit in their own destiny - a favorite trick of sadists everywhere. |

Figure 8. Fall Back into Camp |

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONTraditional theater can integrate objects, images, sounds, texts and characters into a gesamtkunstwerk. Virtual reality can go beyond theater not only by exploiting the irreality of a space with no physical laws, but also by use of a first-person viewpoint to bring the user's own body and personal character into the piece. Projecting the image life-sized on a screen brings the user a physical sense of space and scale; allowing the user to navigate through the space on their own adds the kinesthetic sense of movement, orientation and place. Interactivity, whether through positional triggers or active manipulations of objects, makes users complicit in the dramatic structure of the piece, adding a sense of participation and responsibility for the events that happen to them in the course of their explorations. The artist must understand the emotional effect of each of the virtual spaces on the user, and must organize these scenes into phrases or movements, sequences of scenes that can be combined to create a sense of the classic build up, climax and denouement used in the dramatic structure of theater. If the piece loops, every scene must have enough material to bear several investigations. This insures that each time through the piece users will construct a slightly different narrative, viewing and interacting with the material in a slightly different way, discovering new objects or seeing the same things in a different light as their previous experiences have now become part of their own memories. |

|

|

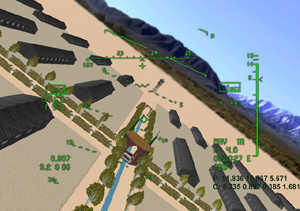

According to Leonard Meyer, it is not enough to provoke emotional states; one must also provide meaningful and relevant resolutions in order to produce an emotional release of the tensions built up within the piece. Although the looping structure of Beyond Manzanar provides no true beginning or ending, it still has a strong dramatic climax followed by resolution. In the "war" scene, Zara played on fears of Iranian Americans that the American bombers used in the Gulf War against Iraq could also be used in some future conflict against Iran. Users are swept up out of an Iranian paradise garden by an F-15. Tumbling in the air, they see the garden now framed by an internment camp - and by the sights of the F-15. |

Figure 9. War |

|

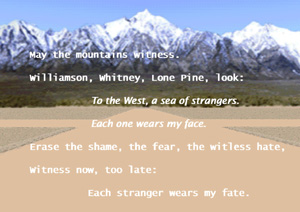

The F-15 finally passes, leaving users spiraling through the air high above the landscape of Manzanar. The "Resolution Poem," written by Zara specially for this piece, then appears against this backdrop. It asks the mountains, winds, earth and sky to bear witness to the history of this place called Manzanar, so its story may never be repeat. Although this piece refers to events and people in the United States of America, we feel that our message is a universal one, applicable to any country anywhere in the world where politicians single out groups as convenient scapegoats in times of crisis. We hope that the experience of Beyond Manzanar goes beyond visual and intellectual stimulation to affect users emotionally, communicating to them a bit of what it means to face discrimination solely on the basis of belonging to a group with "the face of the enemy." |

Figure 10. Resolution Poem, 1st Verse |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSMany thanks to the sponsors who made Beyond Manzanar possible:

REFERENCES

|

|